IN CLIMATE risk rankings, the Philippines is ground zero. Yet, given the choice to redefine the notion of security in 2022, it chose to shun it.

Despite seven decades of climate denialism, funded primarily by the world’s largest energy giants in the United States and, to a lesser degree, in Western Europe, the elevated risks associated with climate change and extreme weather events are today widely recognized.

In the climate risk and disaster rankings, the Philippines is not just any other nation. The disaster-prone archipelago nation is ground zero of climate disaster risk.

World’s greatest disaster-risk zone

The World Risk Index 2025 indicates the disaster risk for 193 countries, or over 99% of the global population. The Philippines is once again at the top of the Index; way ahead of other disaster-prone countries, including India, Indonesia, Colombia, Mexico, and Myanmar.

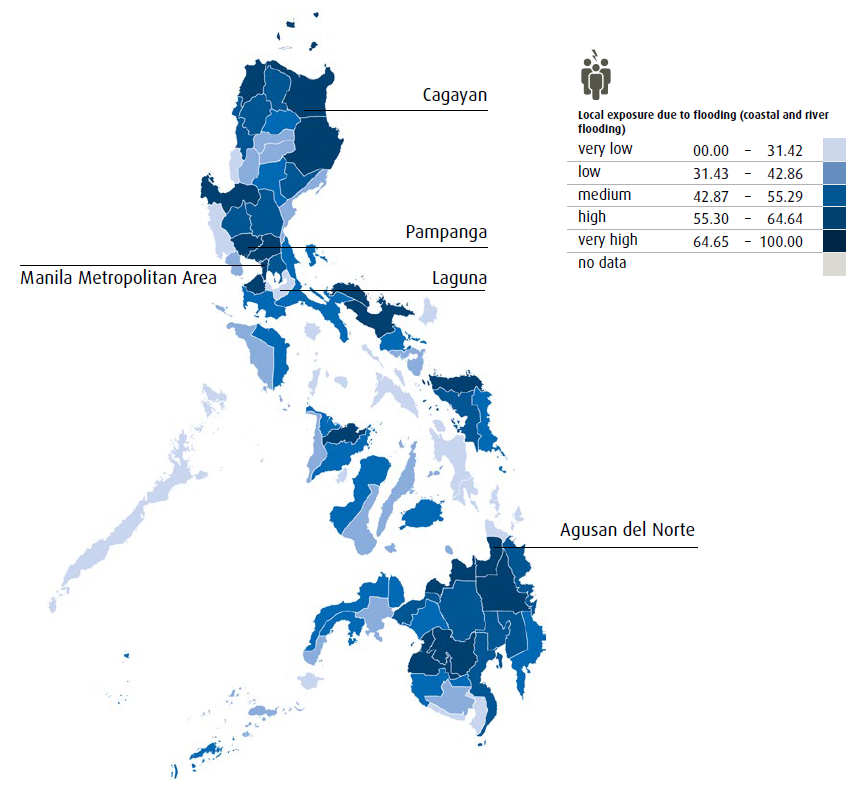

Thanks to its great geographic fragmentation and extraordinarily high exposure to weather-related extremes, the Philippine risk profile is characterized by a variety of natural hazards, with river and coastal flooding playing a particularly central role.

Even before the recent typhoons, the findings showed that the country’s exposure is particularly high in regions with flat topography, high population density, and inadequate drainage infrastructure.

Floods are among the most severe hazards of our time — with devastating consequences for people, infrastructure, and ecosystems. Climate change is exacerbating this threat. And when extreme weather events are on the rise, vulnerable communities are bearing the brunt. In the Philippines, where half of the population defines itself as poor, the implications are severe.

Furthermore, uncontrolled urbanization, industrial agriculture as a driver of soil degradation, and inadequate preventive measures further increase the vulnerability of many regions, not to mention pervasive corruption.

The Philippines is a textbook case of what happens when disaster risk is amplified.

Figure 1 The World Risk Leader: The Philippines

Source: WorldRiskIndex 2025

Increasing GDP losses are coming

Climate change poses major risks for development in the Philippines, with temperature increases, changing rainfall patterns, and rising sea levels that hamper economic activities, damage infrastructure, and induce deep social disruptions. Just one example: According to the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority (NAMRIA), sea level in Metro Manila has risen by an average of 8.4 millimeters a year from 1901 until 2022, almost three times the global average of 3.4 mm/year in the same period.

Projections made by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) suggest that temperatures in the Philippines will continue to increase by about 1-2°C by the end of the 21st century, depending on the climate scenario. (I believe that these estimates may actually prove conservative because the IPCC modeling downplays feedback effects. The climate impact is likely to hit harder, earlier, and broader than expected.)

According to World Bank’s 2022 Philippines report, annual losses from typhoons are estimated to reach 1.2% of the GDP and as much as 4.6% of GDP in extreme cases like Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in 2013. After all, variability and intensity of rainfall are likely to increase. And extreme events will become stronger and more frequent.

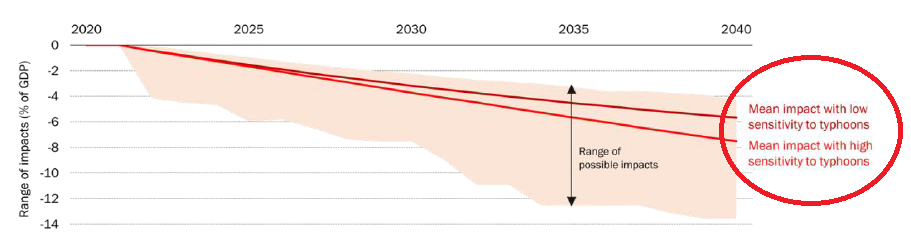

Figure 2 The High Economic and Human Costs to Come

Source: The Philippines World Bank Climate and Development Report, 2022

The economic damages in the Philippines could reach up to 7.6% of GDP by 2030 and 13.6% of GDP by 2040. While climate change effects will vary across and within regions, all sectors will be affected.

And yet, even today, the scarce economic resources in the Philippines are too often misallocated (rearmament drive instead of inter-state diplomacy), mismanaged (neoliberalism instead of human security,) and misplaced (corruption instead of people’s welfare).

As the World Bank warned in 2022, “policy inaction would impose substantial economic and human costs, especially for the poor.”

Could the government have opted for an alternative policy approach that would have tackled the devastating climate losses? Yes. But that approach was deliberately killed – ironically, in the name of national security.

The promise of human security

From the standpoint of disaster risk and extreme climate, one of the most inspiring appointments after the election of 2022 was that of Clarita Carlos to serve as President Marcos Jr’s National Security Adviser. She was the first female and the first civilian to lead the institution.

Upon assuming office, Carlos, a highly-regarded political scientist, planned to undertake a “human security” approach that focuses more on the daily lives of the Filipinos. It was the right idea at the right time and in the right place.

Historically, this broader view of human security builds on the 1994 Human Development Report by the UN Development Program, which equated it “with people rather than territories and with development rather than arms.” [my italics, DS]

Accordingly, threats to human security may be classified into economic, food, health, environmental, personal, community, and political security. This approach would encourage the government to focus its strengths on its greatest enemy: the risk of climate disaster.

But what about the South China Sea tensions? During Carlos’s reign, the Philippines reaffirmed its commitment to international law and the rule of law in inter-state relations. In territorial maritime disputes, Manila would defend its views by being at the forefront of diplomatic efforts aiming at ASEAN-China South China Sea Code of Conduct.

The objective was to ensure peace and stability in the region, while focusing on economic development that had made Asia the global growth engine. That, in turn, is vital to garner the resources to fight the climate disaster risks in the coming decades.

Yet, that’s when the government made its U-turn.

Ignoring the climate focus

In mid-January 2023, Carlos resigned after the president relayed to her “some information” which she could not disclose in public “because it is a delicate national security issue.”

As she acknowledged two weeks later, she had been opposed by the military since day one. In contrast to Carlos, the military saw as the prime security issue “the perceived external threat beyond our shores.”

Barely a day after Carlos’s interview, President Marcos Jr granted the U.S. wider access to military bases. Soon thereafter, the Duterte-Marcos alliance fell apart, mud-slinging superseded politics as usual, former President Duterte was deported to the Hague, ASEAN unity was undermined, geopolitical tensions soared, and Filipinos’ livelihoods were ignored.

The longer it takes to embrace a human security approach, the heavier will be the penalties of disaster risks and extreme weather as the Philippines continues its descent into the ground zero of extreme climate.

But that course is not inevitable. It, too, could be reversed. After all, climate risk is not just a political matter. In the Philippines, it is an existential issue.

—————————————————————–

Dr. Dan Steinbock is an internationally recognized strategist of the multipolar world and the founder of Difference Group. He has served at the India, China and America Institute (USA), Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, see https://www.differencegroup.net