Whenever Philippine–China relations turn tense, familiar calls resurface urging the Philippines to distance itself economically from China and look elsewhere for trade partners. These appeals often lean heavily on trade figures—especially the country’s persistent trade deficit with China—to argue that disengagement is not only possible but overdue.

This pattern is not new. During the Aquino administration, at the height of tensions in the West Philippine Sea, some local officials openly floated calls to boycott Chinese-made products. Similar arguments have returned under the Marcos administration, now reinforced by comparisons between Philippine exports to China and Chinese exports to the Philippines. Today’s “word war” between the Chinese embassy and Philippine officials has once again brought these claims to the fore.

While these concerns are understandable, they are ultimately grounded in a surface-level reading of trade statistics. It is true that the Philippines imports more from China than it exports. Yet treating this imbalance as a stand-alone verdict on the relationship misses the bigger picture. Trade figures do not exist in a vacuum. They are shaped by decades of policy choices, development paths, and the very different ways states manage their economies.

As a political economist and international relations analyst, I argue that a more meaningful assessment of Philippine–China trade must proceed in the following steps. It begins by revisiting how both countries opened their economies in the late 1970s—and how those choices still shape what we trade, and with whom, today.

Same timelines, different directions

China’s rise as a major trade power in the global economy is widely attributed to the series of policy reforms introduced in the late 1970s. In 1978, the Chinese government embarked on what has often been described as a strategy of “selective liberalization.” Rather than pursuing wholesale market opening, Beijing allowed limited and carefully managed forms of privatization, foreign ownership, deregulation, and decentralization, while maintaining state control over sectors deemed strategic or closely linked to national security. These sectors largely remained under the supervision of state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

The cumulative effect of these reforms was transformative—not only for the Chinese economy but also for the Chinese state itself. One of the most visible outcomes was the rapid development of China’s southeastern provinces, which became major recipients of foreign direct investment from firms based in Taiwan, Hong Kong, the United States, and Western Europe.

As China consolidated its manufacturing base through these reforms, it earned the label of the “factory of the world.” The country emerged as a key supplier of intermediate and manufactured goods, embedding itself deeply within global supply chains. Consequently, the transformation of the Chinese economy not only involves participating more fully in international trade through the reduction of tariffs and non-tariff barriers, but also involves shaping global trading regimes. A pivotal milestone in this process was China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001.

The Philippines is no stranger to the economic transformations that propelled China’s rise. During the same decade that China initiated its reform agenda, the Philippines also embarked on liberalization under the administration of Ferdinand Marcos Sr., following policy prescriptions advanced by the United States (US), the World Bank (WB), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Unlike China’s selective approach, however, the Philippine government pursued rapid and relatively comprehensive trade liberalization in the hopes of capturing the promised gains of free trade.

This shift was implemented through a combination of executive orders, legislation aimed at reducing tariffs, state support for export-oriented firms, and participation in regional and global trade arrangements. These included the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (later the WTO), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, and a range of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements within ASEAN. Collectively, these reforms unfolded from the 1970s through the early 2000s, spanning both the Marcos and post-Marcos Sr. administrations.

Beyond export-import trade volumes

The 1990s marked a consequential decade for both countries as they began to experience the long-term effects of liberalization. In the Philippines, the period coincided with economic recovery under post-authoritarian democratic governments following the ouster of Marcos Sr. It was during the administrations of Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos that the Philippines deepened its engagement with the WTO and the ASEAN Free Trade Area.

In China, the 1990s were defined by the leadership of Jiang Zemin, under whom the continuation and expansion of the 1978 reforms became a defining feature of state policy. The resulting economic growth lifted millions out of poverty within two decades—an achievement that many developing economies continue to aspire toward.

Against this background, relying solely on annual export-import figures to judge the Philippine–China trade is misleading. Doing so almost guarantees gloomy conclusions, especially when the focus is on deficits. Worse, this narrow view feeds narratives that turn economic debates into emotional ones, sometimes spilling into outright distrust or Sinophobia.

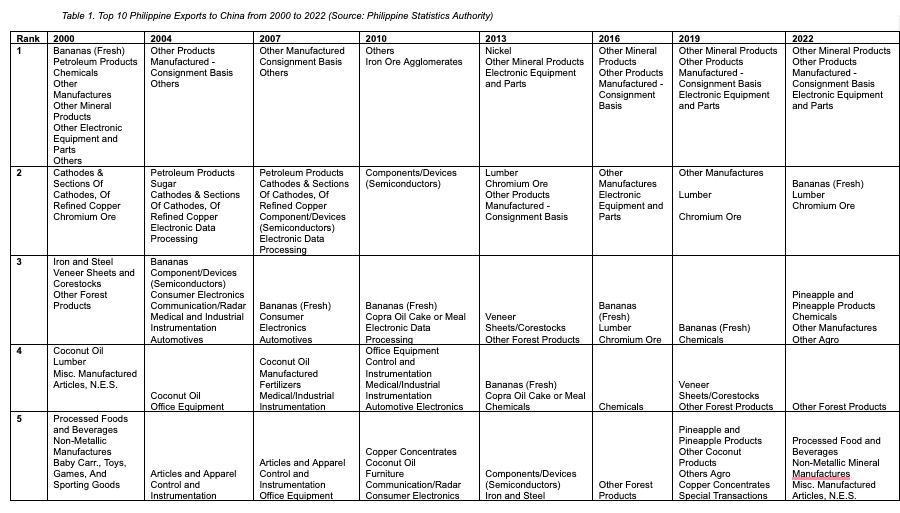

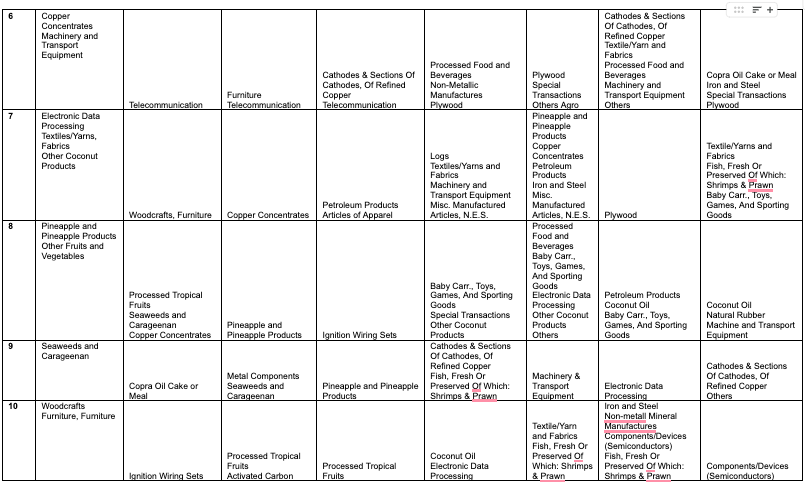

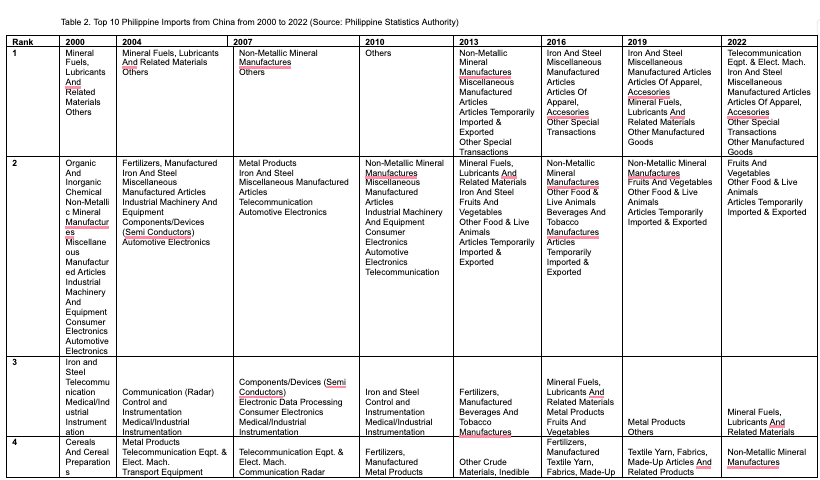

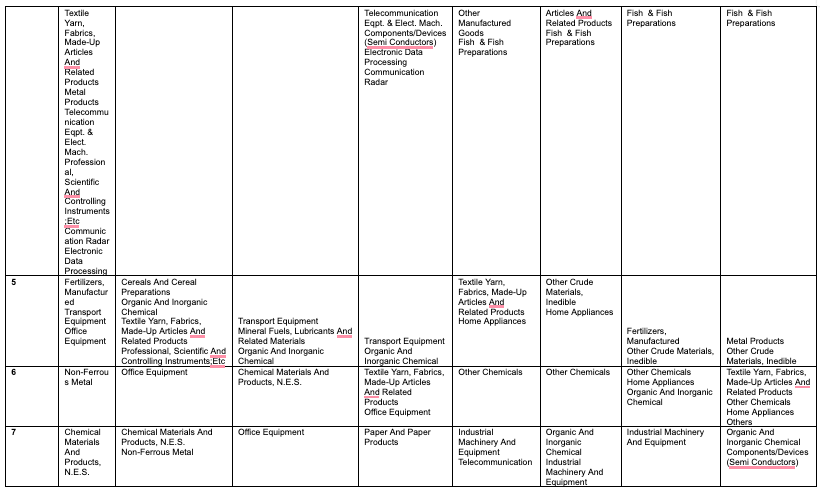

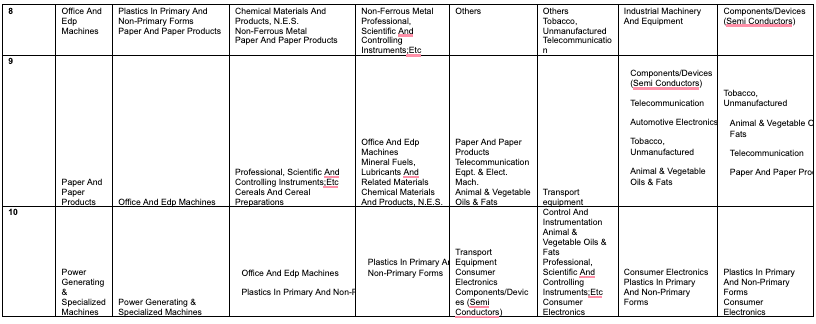

An alternative way of understanding Philippine-China trade relations is to look for the top 10 exports and imports of the Philippines to and from China and contextualize such data in light of Philippine development policies, particularly with the continuation of the export-oriented industrialization (EOI) strategy implemented because of the Philippines’ decision to engage in trade liberalization since the 1970s. Tables 1 and 2 below present a relevant picture of Philippine-China trade relations. Both tables are divided into eight columns which are significant years in the Philippine economic and political histories. For instance, 2000 is the entrance of the 21st Century and the year before China became a member of the WTO. Meanwhile, the remaining years from 2004 to 2022 span the presidencies of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, Benigno Aquino III, and Rodrigo Duterte. Examining the Philippines’ top exports to and imports from China reveals patterns shaped by long-standing development strategies, not just recent political moods. (Note: The rankings presented below are derived from descriptive analysis and have not been subjected to peer review. The author welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive feedback.)

What gets lost in the trade numbers

To understand these patterns, it helps to revisit the Philippines’ development history. From the 1950s to the 1960s, the country followed import-substitution industrialization (ISI), a strategy that protected local industries and limited imports. At the time, the Philippines was seen as one of the more successful cases in the region.

This approach changed in the 1970s, when the Philippines adopted export-oriented industrialization (EOI). The goal was to compete globally by promoting exports, especially manufactured goods. Over time, this divided exporters into two broad groups: traditional exporters, mainly in agriculture and raw materials, and non-traditional exporters, especially in heavy manufacturing and electronics. While both groups remained active, the latter received more policy support and attention from the Philippine government.

In this regard, based on the rankings present in both Tables 1 and 2, the following are five (5) untold stories behind Philippine-China trade relations buried because of the lack of attention given to the economic history of both the Philippines and China. Specifically, these stories affirm the indispensable role of China in Philippine economic development especially that the two Asian partners are no strangers but contemporaries in their quest for mutual prosperity through participation in free trade.

- Philippine-China trade relations affirm the segmentation of Philippine export sector. As presented in both Tables 1 and 2, Philippine exports to China both consist of traditional and non-traditional export goods. Agricultural goods sit alongside electronics and minerals in the country’s top exports to China. This suggests that trade with China supports a wide range of Philippine producers, regardless of who is in Malacañang or how tense diplomatic exchanges become.

- China served as a lifeline for the ailing traditional exporters from the Philippines. For many Filipino development experts, Philippine trade liberalization policies are skewed towards the development of the non-traditional export sector, which primarily consists of firms specializing in electronics and semiconductors. In this regard, debates regarding the preparedness of the Philippines to fully open its economy to embrace globalization took place during the mid- and late 1990s. One of the strong voices that emerged during this period is the anxiety of traditional exporters in the Philippines, especially food producers in Mindanao. However, based on Table 1 ranking, China’s economic liberalization and open-door policy provided a saving grace to Philippine traditional exporters especially agricultural firms specializing in the exportation of high value crops especially bananas, pineapples, sugar and coconut.

- China plays a role in Philippine food security. Development is always uneven and rarely becomes a win-win situation. In this regard, development strategy will always result to “winners and losers” since there will be always be uneven distribution of resources and benefits. In this regard, the Philippine EOI strategy not only resulted to the disadvantage of the agricultural sector. As the Philippines aimed to compete with other states engaged in non-traditional exportation since the 1970s, the Philippine agricultural sector failed to catchup with these rapid developments despite presence of government support, especially through training and technical assistance. As a result, the capacity for food production and supply is affected. In this regard, by looking at Table 2, agricultural and food products frequently land in the top 5 imports of the Philippines from China since 2000. In this regard, it is safe to assume that China also contributes, to a certain extent, to Philippine food security.

- China has become an indispensable destination for sustaining the Philippines’ export-oriented industrialization strategy. Table 1 reveals that, since 2004, Philippine exports to China have shifted from agricultural products to non-traditional export goods, especially electronic parts and minerals. Such changes indicate that the demand from the Chinese market provided additional impetus for the Philippines to sustain its EOI development strategy since the country no longer solely relies on Western markets for its non-traditional exports.

- Imports from China are essential parts of the Philippine domestic supply chain to sustain its EOI development strategy. Per Table 2, both the Philippines and China supply each other with the necessary intermediate goods (e.g. electronic parts, equipment, etc.) in order for both economies to produce their non-traditional exports. While it was established that the Philippines imports more from China and not vice versa and these imports are also those goods belonging to the non-traditional exports, it is wrong to simply assume that the Philippines is suffering from unfair and unequal trading terms with China because of annual negative scores in terms of balance of payments (also known as trade deficit). This is a very simplistic and reductionist assumption. Imports from China indicate that these are also non-traditional export goods, which can be assumed to also support the operations of the Philippine-based non-traditional exporting sector, mostly located within special economic zones (SEZs) across the country. A multiplier study covering the forward and backward linkages of Philippine non-traditional export sectors may confirm this claim.

Conclusion

The renewed exchange of sharp words between Chinese diplomats and Philippine officials has once again pushed trade into the political spotlight. In moments like this, it is tempting to treat trade figures as straightforward proof of dependence or vulnerability.

But trade numbers are not self-explanatory. They reflect long histories of policy choices, development strategies, and economic priorities on both sides. Reading them without that context leads to conclusions that are easy to repeat but hard to defend.

If the Philippines wants a clearer view of its economic relationship with China—especially during periods of diplomatic strain—it must resist the urge to rely on quick comparisons and headline figures. A more careful reading, grounded in history and development experience, offers a steadier basis for debate and for policy decisions in an increasingly complicated regional environment.

Brian U. Doce is a scholar-practitioner with a background in politics and international relations. He lectures at several universities in Metro Manila and has extensive experience in business–government relations, policy advocacy, and diplomacy. He may be reached at scholarbud@gmail.com.